Friday, December 28, 2007

I'm Dreaming...

How Do You Feel About That?

"Now do you understand what Rich meant?": "Susan/Eulogos, one of my most insightful commenters, took a look at the article on the Cincinnati RCIA conference about which I posted the other day.

She does not like what she saw.

There was not one word in this article about teaching the content of the Catholic faith. The Catechism was not mentioned. The creeds were not mentioned. Dealing with typical difficulties and objections was not mentioned. A question of minimum standards for knowledge was [not] mentioned. No discussion of how much content was necessary or appropriate for people of different educational backgrounds. No discussion of what people are actually agreeing to when they assent to 'everything the Church teaches.' (Or to saying that everything the Church teaches is revealed by God, which ought to be the same thing.) No sessions about how to guide those who can accept 'everything except Papal Infallibility' or 'everything except the Immaculate Conception' or 'everything except no contraception.' I would think that these sorts of subjects would need to be discussed by RCIA people. But instead, according to the article, it was all about what parts of the RCIA program 'mean to me.' Suggesting an echo of RCIA programs which are all about 'What being a Catholic means to me?' (You know, 'For me, it is all about being part of a big family' or 'Its all about the community.' etc etc.)"

(Via Ten Reasons.)

Cherchez

Six injured by exploding fondue: "Three people are taken to hospital with serious burns after a gas-powered fondue set explodes."

(Via BBC News.)

Wednesday, December 19, 2007

What Child is This?

Looking for Mary in Christmas Carols: "It’s Christmas, so we’re singing carols. OK, it’s not Christmas, it’s really Advent, and “carol” has a particular set of musicological meanings that don’t have anything to do with Christmas–but we call almost any tune we sing in December a “carol” (even that culinary chestnuts song) and the speaker at the stand where I pump [...]"

(Via FIRST THINGS: On the Square.)

Christmas Preparations

The Magi and Their Scientific Discovery: ""

(Via New Advent World Watch.)

Friday, December 07, 2007

A Day Late...

Shame on me for neglecting one of my favourite saints: belated Happy Nicholmas to all!

Thanks to Rachel Watkins at Heart Mind & Strength.

Up for Air

I quickly finished John Finnis' Fundamentals of Ethics

This family of ethical systems barely rated a mention in our course, and then simply as Command Law ethics. You know, God says it so we have to do it. The strong implication is that this a purely religiously based ethical system. Cicero would have been surprised.

Having seen Alasdair Macintyre mentioned around the web, and particularly in First Things, I had a go at After Virtue

And now I'm going through Gomez-Lobo's Morality and the Human Goods

And my copy of Finnis' Natural Law and Natural Rights

Now I have to get off philosophy (the final is in a little over a week from now) and read P.D. James' The Children of Men

Good Reading!

Thursday, December 06, 2007

In the Interim

The Case Against Abortion: An Interview with Dr. Francis Beckwith: "

The Case Against Abortion: An Interview with Dr. Francis Beckwith, author of Defending Life | Carl E. Olson | December 5, 2007

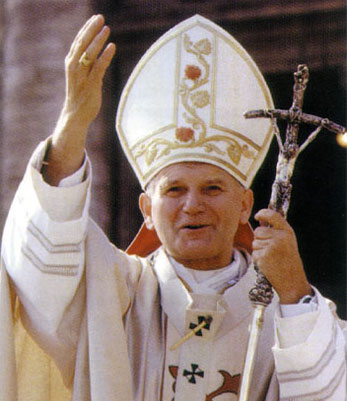

Dr. Francis Beckwith (personal website), Associate Professor of Philosophy at Baylor University, made

news this past May when he publicly announced that he had returned to the

Catholic Church after spending over thirty years in

Evangelical Protestantism.

But Dr. Beckwith has been receiving attention more recently for his latest

book,

Defending Life: A Moral and Legal Case Against Abortion Choice (Cambridge University Press, 2007), a thorough and

impressive work that engages and responds to the many arguments—both

popular and scholarly—given by abortion rights advocates.

Rev. Richard John Neuhaus of First Things stated of Defending Life:

'By a masterful marshalling of the pertinent arguments and a civil engagement

with the counter-arguments, Beckwith makes a convincing case for law and social

policy based on reason and natural rights rather than the will to power.' And

in a November 26, 2007, column in America magazine, noted bioethicist Fr. John F. Kavanaugh, S.J.,

professor of philosophy at St. Louis University, wrote that Dr. Beckwith 'charitably and

thoroughly engages those who oppose him. Defending Life is a model of how a pro-life position is effectively

mounted. One might hope that defenders of abortion would as thoughtfully engage

his arguments. I at least hope that our own bishops will take up this work and,

upon reading it, offer it to every parish library in the country. They might

also request that lay leaders, especially physicians, lawyers, teachers and

business persons, enlist such a book in their efforts not only to form their

own consciences, but also to inform and elevate the somewhat cheapened and

knee-jerk moral discourse over the issue of abortion.'

Carl E. Olson, editor of Ignatius Insight, recently interviewed Dr. Beckwith

and spoke with him about his book, the state of the pro-life movement, and how

those who oppose abortion can better take a stand against the culture of death.

Read the entire interview...

Friday, November 23, 2007

Something to Ponder

Recommended Reading: The Heart Has its Reasons: Examining the Strange Persistence of the American Death Penalty

Studies in Law, Politics and Society, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2008

Abstract:

The debate about the future of the death penalty often focuses on

whether its supporters are animated by instrumental or expressive

values, and if the latter, what values the penalty does in fact

express, where those values originated, and how deeply entrenched they

are. In this article I argue that a more explicit recognition of the

emotional sources of support for and opposition to the death penalty

will contribute to the clarity of the debate. The focus on emotional

variables reveals that the boundary between instrumental and expressive

values is porous; both types of values are informed (or uninformed) by

fear, outrage, compassion, selective empathy and other emotional

attitudes. More fundamentally, though history, culture and politics are

essential aspects of the discussion, the resilience of the death

penalty cannot be adequately understood when the affect is stripped

from explanations for its support. Ultimately, the death penalty will

not die without a societal change of heart.

(Via Mirror of Justice.)

Thursday, November 22, 2007

Confession Time

Why NOT Embryonic Research?: "

I heard about this new stem cell research yesterday on NPR, which broadcast a brief debate on the subject between Sean Tipton, president of the Coalition for the Advancement of Medical

Research, and Richard Doerflinger, deputy director of Pro-Life

Activities for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Basically, Dr. Doerflinger takes this advance as Great News in that soon there may be no scientific (let alone moral) justification to continue controversial research on human embryonic stem cells, whereas Dr. Tipton thinks such research should continue - just in case. He sees stem cell research as a race to the finish line (his analogy) and whatever it takes to get there is fine, even though 'some people' have moral problems with it.

It wasn't so much his point of view that puzzled me (after all, you can't expect someone who doesn't believe in moral absolutes to behave as if they do*) but the way he defended it; So, why should we continue with controversial research, even in the face of grave moral misgivings? Because 'we live in a pluralistic society'.

H'okay...

Now, I'm sure Dr. Tipton could give a better, more well-rounded defense than that, if pressed, but tho whole idea (very popular, of late) that a 'pluralistic society' must allow scientists to pursue 'whatever works' is just freaky.' Never mind advanced ethical philosophy, has Dr. Tipton never seen Frankenstein or Them or even The Hideous Sun Demon? Hollywood had this all sussed many decades ago... there are Some Things that Man was Not Meant to Tamper With.

And, the question must be asked; if Moral Pluralism is the standard, the foundational dogma of our modern society, then what is NOT to be allowed, and why? Aren't all ethical frameworks equally - that is subjectively - valid? Why NOT eugenics? Why NOT a genetically modified warrior race? Why NOT chemical and biological weapons?

The natural law would proscribe all these things on the basis that they are offenses against human dignity. Pluralism might find them all wrong now (because most people find them morally repugnant, even if they can't say why), but there can be no guarantee about the future. If most people' - or even if enough of the right people - become okay with it at some point, well, we can expect these kinds of examples of the New, Improved Dynamic Morality.

'How beautious mankind is! O brave new world: That has such people in't!'.

*This touches on a recent mammoth combox debate on morality and ethics. There is this idea that one may arrive at a workable moral framework in a number of ways and that there will be little practical difference in the end. But that is not true. Toss out moral absolutes and the divergences in ethical philosophy and practice are profound and immediate.

(Via JIMMY AKIN.ORG.)

Monday, November 19, 2007

Reading?

And over the weekend, I read John Finnis' Fundamentals of Ethics

Since he left open the possibility that Virtue Theory might have an argument against euthanasia, I tried reconstructing the argument, based loosely on what I read here. In a way, it's too bad that question didn't come up. I put so much effort into it. On the other hand, it was long and involved. And I barely finished the exam on time as it was. C'est la guerre.

MId-Term

The Two Most Important Philosophers Who Ever Lived: "

The Two Most Important

Philosophers Who Ever Lived | Peter Kreeft | The Introduction to

Socrates Meets Descartes: The Father of Philosophy Analyzes the Father of Modern

Philosophy's Discourse on Method

Introduction

This book is one in a series of Socratic explorations of some of the Great

Books. Books in this series are intended to be short, clear, and non-technical,

intended to be short, clear, and non-technical,

thus fully understandable by beginners. They also introduce (or review)

the basic questions in the fundamental divisions of philosophy (see the

chapter titles): metaphysics, epistemology, anthropology, ethics, logic,

and method. They are designed both for classroom use and for educational

do-it-yourselfers. The 'Socrates Meets . . .' books can be read and understood

completely on their own, but each is best appreciated after reading the

little classic it engages in dialogue.

The setting – Socrates and the author of the Great Book meeting in

the afterlife – need not deter readers who do not believe there is

an afterlife. For although the two characters and their philosophies are

historically real, their conversation, of course, is not and requires

a 'willing suspension of disbelief '. There is no reason the skeptic cannot

extend this literary belief also to the setting.

This excerpt is the Introduction to Socrates

Meets Descartes.

Socrates and Descartes are probably the

two most important philosophers who ever lived, because they are the two who

made the most difference to all philosophy after them. Socrates is often called

'the Father of Philosophy' and Descartes is called 'the Father of Modern

Philosophy.' The two of them stand at the beginning of the two basic

philosophical options: the classical and the modern.

At least seven features unite these two

philosophers and distinguish them from all others.

Continue reading...

Thursday, November 15, 2007

Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others

China

I'm getting the usual pre-test jitters (Mid-Term #2). I'll try to get through the paralysis and do creditably well on Monday. Anyway, that's the excuse for the lull in blogging.

The two issues to be dealt with on the mid-term are Abortion and Euthanasia, as my readers no doubt have noticed. I'm at least better prepared than the average fresh-out-of-high-school classmate, in that I've done reading and thinking about these topics for some decades. But formulating and properly critiquing arguments to a freshman standard is a challenge. But that's the point of an education, right? (To be intellectually challenged, I mean.)

Thursday, November 08, 2007

Will Women Be More "Valuable" in the Future?

Acrimony

At what point does the state of ignorance end or the manifestation of wickedness begin within each individual who comes to abhor anything considered Pro-life? When or how does one cross-over from a distorted sense of altruistic compassion into the realm of the wicked? A New York Times article which featured an abortionist named Dr. Susan Wicklund brought this to mind.

At what point does the state of ignorance end or the manifestation of wickedness begin within each individual who comes to abhor anything considered Pro-life? When or how does one cross-over from a distorted sense of altruistic compassion into the realm of the wicked? A New York Times article which featured an abortionist named Dr. Susan Wicklund brought this to mind.

While the article starts off with a somewhat negative connotation towards abortion, it eventually becomes apparent that the NY Times is setting Wicklund up as some sort of twisted mother of mercy. It’s the times! To me, there’s something even more so wicked when those in positions of authority and trust employ techniques of establishing a false sense of security and trust, only to draw victims into the corruption of their lies and deceit. Whether or not she believes in her own lies is of little concern to me, as opposed to the prevalence of liars who perpetuate and create the lies and deception which is responsible for a crime which is one of the most despicable acts one human could ever inflict on to another. Among her claims to promote a normalcy for abortion:

40% of American women have abortions.

More common that the removal of wisdom teeth.

Abortion restrictions are about the control of women, about power, and it’s insulting.

Protesters who regularly appear shouting outside abortion clinics also get abortions.

Abortion give women back their life, their control.

In addition to Susan’s apparent deficiencies simple math, is another example to remember that figures don’t lie, but liars do figure, and yet more proof of funny numbers and protecting sex offenders.

"(Via COSMOS-LITURGY-SEX.)

Arguments and Logic

On another night, bioethicist Lee Silver from Princeton visited the show. Colbert told him he believed that science and spirituality could go hand in hand and that all people, embryos included, have souls. Silver begged to differ. He told Colbert that, in the shower, we scrub off thousands of skin cells every day, and that the cells on his arm are human life in the same way that embryos are. To which Colbert responded: “If I let my arm go for a while and didn’t wash it, you’re saying I’d have babies on my arm.” Thank goodness we have comedians to take such arguments to their natural conclusions.

Thanks to Nathaniel Peters at First Things.

Freedom and Virtue

The Illusion of Freedom Separated from Moral Virtue: "

The Illusion of Freedom Separated from Moral Virtue | Raymond L. Dennehy, University of San Francisco

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the Journal of Interdisciplinary

Studies (Vol XIX, 1/2 2007), and is reproduced here by the kind permission of JIS. It won the Oleg Zinam Award for Best

Essay in JIS 2007.

This essay proposes that

liberal democracy cannot survive unless a monistic virtue ethics permeates

its culture. A monistic philosophical conception of virtue ethics has its

roots in natural law theory and, for that reason, offers a rationally

defensible basis for a unified moral vision in a pluralistic society. Such

a monistic virtue ethics--insofar as it is a virtue ethics--forms

individual character so that a person not only knows how to act, but

desires to act that way and, moreover, possesses the integration of

character to be able to act that way. This is a crucial consideration, for

immoral choices create a bad character that inclines the individual to

increasingly worse choices. A nation whose members lack moral virtue

cannot sustain its commitment to freedom and equality for

all.

FREEDOM AND VIRTUE

The thesis defended in this

essay is that liberal democracy cannot survive unless a monistic virtue

ethics permeates its culture. Two arguments are given in its support.

First, a monistic philosophical conception of virtue ethics has its roots

in natural law theory and, for that reason, offers a rationally defensible

basis for a unified moral vision in a pluralistic society. Second, a

monistic virtue ethics--insofar as it is a virtue ethics--forms individual

character so that one not only knows how to act, but desires to act that

way and, what is more, possesses the integration of character to be able

to act that way. This is a crucial consideration, for immoral choices

create a bad character that inclines the individual to increasingly worse

choices. A nation whose members lack moral virtue cannot sustain its

commitment to freedom and equality for all.

Read the entire essay...

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

More of the Same

The philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson has famously argued that even if human fetuses are persons with rights (as she is willing to concede they are from a fairly early point in development), those rights do not entail an obligation on the part of pregnant women to continue nourishing them. But as I note in the book, this defense is false to the nature of abortion. Perhaps it would work if abortion were a mere eviction from the womb. But the death of the fetus is in nearly every real case the goal of an abortion, and it is always the means to whatever its goal is.

As for the "Not all humans are persons" line of arguing, he says:

Neil Sinhababu...takes the view that not all human organisms are persons with rights, that there are human non-persons—a view I consider both wrong and dangerous. He believes that I am placing too much importance on the humanity of the human fetus. If the right to life attaches to any organism that happens to belong to the human species, he asks, then what would happen if we met intelligent extraterrestrial life? “To ground moral status in biological humanity is to shrug at the enslavement of hobbits, the slaughter of kittens, and the destruction of all life beyond earth.” Nice line—but no. From the premise that all human beings have a right to life it does not follow that all non-human beings lack it. Humanity is a sufficient condition for having the right to life, but not a necessary one. I even mention, in a footnote, that an alien could have the right to life. The key question would be whether those aliens have a rational nature, as humans do. Indeed, my premises would allow for more protection of those aliens than Sinhababu’s theory would. He believes that human beings and other types of beings have value to the extent that they have the immediately exercisable capacity to perform mental functions. That would leave immature or handicapped aliens, hobbits, and humans without protection.

Ponnuru's conclusion is hopeful:

In 1970 and for many years thereafter, advocates of legal abortion portrayed themselves as the party of cool, dispassionate reason. Their opponents were the prisoners of superstition and emotion. Pro-abortionists back then tried—not, I think, well—to argue either that fetuses were not “alive” or “human” or that their killing could be justified philosophically.

Today, they tend with few exceptions either to refuse to engage the argument at all or to retreat behind their feelings and other non-rational defenses. There are, of course, very smart people on the other side of the debate. But I think The Party of Death and the reaction to it demonstrate something else that has changed in the last four decades: The intellectual high ground is now ours.

Read the whole thing (if you can stand pdf).

Thanks to Kevin Miller at HM&S.

Monday, November 05, 2007

Good News and Bad News

Thanks to Kevin Miller at Heart, Mind & Strength.

Who Reads More?

It's interesting that he uses the parallel of the now largely unregulated air travel industry as an example of good things happening for the consumers. It just reminded me of how unhappy some of the airline employees are now, feeling that their jobs have been degraded in pursuit of the bottom-line lowest price.

In any case, the title question has some ambiguity in it. Apparently there are more books published in Germany than in the U.S., even though the U.S. has four times the population. So do Germans read more than Americans? Or do some Germans (the relatively wealthy) skew the publishing numbers because the effective cartel-pricing imposed by the government, causes competition in otherwise more expensive titles?

Trouble is, I'm still wrestling with some of the pro-abortion arguments. And today we started grappling with euthanasia arguments. No room in this old-style processor for so much input. But it is intriguing.

Friday, November 02, 2007

How to An Create Urban Legend

The only remotely sympathetic characters that are explicitly religious on these shows are "cool", "hip" priests and nuns, who couldn't inspire religious fervour in anyone, much less real Christians. Just the sort of religious people the elite finds tolerable. All other characters with religious convictions are:

1. neurotic,

2. murderous,

3. unpleasantly, even inhumanly, cold,

4. stupid or ignorant, or

5. some combination of the above

Which tells me that the people producing the shows have never met, or at least never recognized, a well-adjusted, law-abiding, compassionate, intelligent and well-educated Christian. (Muslims generally get a pass from L&O, but that's another story.) From which lack of experience they must conclude that such people don't exist or are very rare.

So, associating anti-abortionism with religious beliefs, they project these characteristics onto the appropriate characters. And burning, bombings, and murders are the result.

And everybody knows that a) anti-abortionists are violent and that, b) they burn and bomb abortion clinics.

Speaking of ancient civilization

Philosopher thinks polytheism (many gods) would be an improvement - really!: "Here's something you don't see every day: A defence of polytheism. Arguing that 'Mere mortals had a better life when more than one ruler presided from on high', professor emerita Mary Lefkowitz of Wellesley College argues that we should 'Bring back the Greek gods':

The existence of many different gods also offers a more plausible account than monotheism of the presence of evil and confusion in the world. A mortal may have had the support of one god but incur the enmity of another, who could attack when the patron god was away. The goddess Hera hated the hero Heracles and sent the goddess Madness to make him kill his wife and children. Heracles' father, Zeus, did nothing to stop her, although he did in the end make Heracles immortal.

But in the monotheistic traditions, in which God is omnipresent and always good, mortals must take the blame for whatever goes wrong, even though God permits evil to exist in the world he created.

Et cetera. Actually, polytheism was rejected in the Western tradition for two reasons: First, it seemed illogical (irresistible force meets immovable object?). Second, the capricious qualities of the old gods, which Lefkowitz admires, were despised among the people.

Interestingly, during the Christian era, many of the gods found a second career as fairies, goblins, and witches - which doubtless suited them well enough. The opera Tannhauser offers a look at this process.

More generally, I have difficulty with the idea that anyone today would actually BELIEVE polytheism. I wish I could remember the name of the Canadian feminist philosopher who pointed out that problem years ago. Christians actually believe in the Triune God, even though we can't entire grasp the relationships involved in the Trinity. But no one could believe in the same way - in Venus or Mars or Bacchus. They merely represent our own states of mind to ourselves.

And there is a sense in which the pagan gods were never any more than that, even in antiquity. They were not beyond us, they were usually beneath us. So today, a polytheist must be a practical atheist. I do concede Lefkowitz this, however - polytheism is much more fun than atheism, and produces vastly better art and culture. Compare, for example, the monstrosities of totalitarian atheist architecture in the twentieth century with the Parthenon of ancient Greece."

(Via Mindful Hack.)

Quibbles

One of the recurrent themes I'm picking up in reading the pro-abortion essays--ok, I'd better stop and explain my terminology. While I prefer Pro-Life as a description, it is true that both this and Pro-Choice are rhetorical names. They try to project the positive about their position. Plus there's an unspoken feeling on both sides that abortion names an unpleasant topic and so is best left unmentioned. For the purposes of philosophy I'll restrict myself to pro-abortion to designate those arguing for fewer or no legal restrictions on abortions; and anti-abortion for those favouring greater or almost complete legal restrictions on abortion.

Back to the original point: there's a recurrent theme in pro-abortion arguments, not part of the argument directly, but alluded to again and again: "We're the compassionate ones!" There may, in fact, be some objective basis for this assertion, though it's initially counter-intuitive to me. "We favour killing the unborn because we're such feeling people. Not like those cold, heartless anti-abortionists." This is a rhetorical device and, no doubt, reflects the beliefs of many, even most, pro-abortionists when dealing with their opponents.

The occasion of this complaint, however, is a remark by Warren in her essay, when forced to confront the reality that her argument, to be successful, must also include infanticide:

Throughout history, most societies--from those that lived by gathering and hunting to the highly civilized Chinese, Japanese, Greeks, and Romans--have permitted infanticide...regarding it as a necessary evil. [emphasis added]

Wikipedia limits itself to saying many, rather than most, societies permitted infanticide. So the "everybody did it" element of the premise is suspect. But move on to the emphasized section: I have no knowledge of history to speak of, and certainly none of the practice of infanticide amongst civilized Chinese, Japanese, and Greeks. But I have certainly heard of pater familias amongst the pagan Romans. And so I'm bound to ask: what sources indicate the the Romans (or any of the other civilizations cited) found infanticide a necessary evil? Consider this:

A letter from a Roman citizen to his wife, dating from 1 BC, demonstrates the casual nature with which infanticide was often viewed:

"Know that I am still in Alexandria. [...] I ask and beg you to take good care of our baby son, and as soon as I received payment I shall send it up to you. If you are delivered [before I come home], if it is a boy, keep it, if a girl, discard it." – Naphtali Lewis, Life in Egypt Under Roman Rule.[4].

In some periods of Roman history it was traditional in practice for a newborn to be brought to the pater familias, the family patriarch, who would then decide whether the child was to be kept and raised, or left to death by exposure. The Twelve Tables of Roman law obliged him to put to death a child that was visibly deformed.

It's interesting to note that the major monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) all reject infanticide explicitly. That's one reason for Warren to reach back to the pagan past for her civilized examplars. Current examples of legalized infanticide are not presented by Warren, monotheistic or otherwise. And the gendercide going on in India and China currently is happening primarily in the hinterlands, amongst the uneducated and least civilized. But what of the civilized Romans?

This phrase ("regarding it as a necessary evil") seems to me to be a rhetorical phrase that attempts to paint the ancients as both wise (so we'll be persuaded to follow their example) and compassionate (so we can be assured that they were people like us). The evidence for this regret is a little thin on the ground, however. A civilization, such as the Romans, that used crucifixion for non-Romans (always preceded by a scourging that defies description), found entertainment in convicts being killed by wild animals (damnatio ad bestias), and that mandated the exposure of defective newborns, doesn't strike me as one that found infanticide as the least bit evil, though certainly necessary.

Of course, I'm open to persuasion to the contrary if evidence is produced.

Thursday, November 01, 2007

When is Enough, Enough?

My first visit to the Sistine Chapel happened in my callow youth. We were in Rome for five days and the visit was coming to an end. So I rushed over to the Vatican Museum, walked quickly through it, passed through the Sistine Chapel on the way out, pausing briefly to look up.

As the years went by, this memory bothered me more and more. So on my second visit, this time with my beloved, I took a book giving some details of the Chapel's frescoes and a small pair of binoculars. After a leisurely stroll through the Museum we moved over to a wall of the Sistine and waited patiently for a bench space to open up. We then sat for twenty minutes, trying to take it all in. I felt much better.

Until today, sigh:After hours at the Vatican Museums: "

There’s nothing quite like an evening book presentation inside the Vatican Museums. It’s a thrill just to walk through the darkened museum hallways at night, hours after the place has officially closed. Last Tuesday, there was the added spectacle of a thunderstorm raging outside. I headed to the conference hall, strolling past Egyptian mummies, Roman mosaics and rows of imperial busts that came to life with each flash of lightning. It felt like the opening of ‘The Da Vinci Code.’

The book presentation took place under the watchful eye of Augustus in armor on one side and a nude satyr on the other. As I settled in for the inevitable round of speeches, the question occurred to me: Who needs another book on the Sistine Chapel? This one was written by a German Jesuit, Father Heinrich Pfeiffer, who spent nearly 50 years investigating the religious images and symbols of the Sistine frescoes. His thesis turned out to be interesting, though: while modern experts tend to focus on the artistic vision and style of the chapel’s painters, including Michelangelo, the artists actually worked according to quite specific parameters set by papal theologians. As a result, Father Pfeiffer says, the chapel is really a study in Renaissance Christian iconography.

The bonus postscript to the speechifying was a private visit to the Sistine Chapel. As we all stood around craning our necks, Bruno Bartoloni, the longtime Vatican correspondent for Agence France-Presse and Corriere della Sera, took me aside and pointed to a spot halfway up the wall. There, camouflaged in a fresco of drapes, was a rectangular ‘peephole’ used by popes who wanted to watch over liturgies without being seen. Bartoloni, who has visited nearly every square inch of the Vatican’s jumbled geography, said he’d once stood inside the tiny papal hideaway.

It was still raining the next day when I returned to the Sistine Chapel during tourist rush hour. I wanted to see how the Vatican was handling the increasingly huge crowds that pour into the museum. The Sistine, of course, was shoulder-to-shoulder. A U.S. couple told me they had waited an hour and a half in line just to get into the museum; now, standing beneath one of the world’s artistic masterpieces, they felt like they were riding a crowded Roman bus. I don’t think they caught many of the frescoes’ iconographical details.

Back home, they might want to check out Father Pfeiffer’s book, ‘The Sistine Chapel: A New Vision.’ And those who can’t afford the volume’s high price tag can always view parts of the chapel online at the Vatican’s Web site.

Back home, they might want to check out Father Pfeiffer’s book, ‘The Sistine Chapel: A New Vision.’ And those who can’t afford the volume’s high price tag can always view parts of the chapel online at the Vatican’s Web site.

(Via New Advent World Watch.)

A Philosophical Approach to Abortion

The arguments for the morality of abortion have one common element. They deny that all human beings are persons (rights holders). (Thomson may be an exception, but her position isn't all that popular in pro-abortion circles). Warren uses analogical arguments (thought experiments) to sketch out her particular view of how we can decide who is human and who isn't. Keep in mind that she is a Contractarian, and believes that rights are something we agree to create. She denies, effectively, the truth of: "All Men are Created Equal". In this sense, she is sketching out a possible method for deciding which human beings we can agree are persons [like us], and which are not.

So let's take one of Professor Peter Kreeft's versions (while speaking at Georgetown University, 10/19/06) of the anti-abortion argument, so we can see what it looks like:

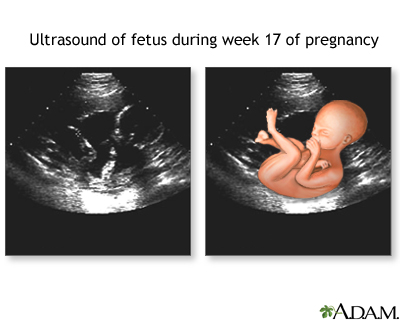

1. The life of each individual member of a species, at least mammalians, begins at conception [fertilization].

2. All humans have the right to life because they're all human persons. [We all share human nature, therefore, we all, all things being equal, share the same universal human rights.]

3. The law must protect the most basic human rights of all it's citizens.

______________

4. Therefore, the law should forbid the direct killing of pre-born humans [zygotic, embryonic, and foetal humans] the same as it protects the life of humans after birth [infant. child, adolescent, adult, aged, and dying humans].

Early pro-abortion approaches tried to deny the first premise. But that is uncontroversially true as a scientific fact. The main focus is now on denying the second premise. The rub is that there is no justification for killing humans before birth that doesn't apply equally to infants (and others) after birth. The grisly result of stubbornly defending the intuition that abortions must be justified is the reality that pro-abortion thinkers, to be be consistent, must, with some greater or lesser enthusiasm, embrace infanticide and euthanasia.

And cobbling together a denial of the [moral] humanity of the unborn while trying to stop sex-selection abortions is a feat worthy of a philosophical Rube Goldberg. Maybe some foetuses are more equal than others?

Monday, October 29, 2007

Viability

If Only They Could Get Married, If Only They Would Let Women...

"And no one - not the schools, not the courts, not the...: "'And no one - not the schools, not the courts, not the state or federal governments - has found a surefire way to keep molesting teachers out of classrooms.'

The answer is obvious: let teachers marry and let women be teachers."

(Via Catholic and Enjoying It!.)

The Moral Community

Therefore, a law prohibiting abortion would unjustly impose one's morality upon another only if the act of abortion is good, morally benign, or does not unjustly limit the free agency of another. That is to say, if the unborn entity is fully human, forbidding abortions would be perfectly just, because nearly every abortion would be an unjust act that unjustly limits, or more accurately, does not permit to be actualized, the free agency of another. Consequently, the issue is not whether the pro-life position is a moral perspective that may be forced on others who do not agree with it, but rather, the issue is who and what counts as "an other," a person, a full-fledged member of the human community. (pp 118-9)

Now the article itself:

Dr. Beckwith on defining "pro-life": "

In a post yesterday, I had a quote from Dr. Francis Beckwith's Defending Life: A Legal and Moral Case Against Abortion Choice (Cambridge, 2007), which is a very thorough apologia against abortion rights and for the pro-life position. Today's edition of the Waco Tribune-Herald has an op-ed by Dr. Beckwith, titled 'Let us define 'pro-life' for you.' He writes:

"What then is the pro-life

position? It is the view that the membership of the human community

includes prenatal human beings, even if excluding them would benefit

those who are more powerful than the prenatal and who believe that the

prenatal’s destruction is in their interest.It is the view that human beings have intrinsic dignity by nature

that is not a consequence of their size, level of development,

environment or dependency.'Young writes: ‘Surely someone devoted to preventing abortions would be just as devoted to preventing pregnancy.’

Pro-lifers, to be sure, would like to see fewer abortions. But it is

not because we find abortion unattractive or repugnant, as if judging

its wrongness were merely a matter of like or dislike.Rather, the reason why we would like to see fewer abortions is

because the unborn are full members of the human community and ought to

be respected as such.Once a human being comes into existence, the parents have an

obligation to care for this vulnerable and defenseless family member.

These parents may call on the rest of us to help and provide to them

both material and spiritual resources, as many pro-life groups and

individuals indeed do.

(Via Insight Scoop | The Ignatius Press Blog.)

This is the substance of the disagreement between the pro- and anti-abortion positions: are there (genetic) human beings who are not moral human beings ("persons")? The first side enthusiastically answers: Yes! Their opponents deny that this distinction is valid or helpful.

So now we are considering Warren's Space Traveller thought experiment, which she thinks justifies identifying persons outside of simple biological humanity. There are, of course, some arguments for rejecting this analysis. But for now the need is to understand how analogical arguments work and how to critique them.

Sunday, October 28, 2007

Gird Up Your Loins

Why the Bewilderment? Benedict XVI on Natural Law: "

Why the Bewilderment? Benedict XVI on Natural Law | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J. | October 27, 2007

I.

On October 5, in the Hall of the Popes in the Vatican,

Benedict XVI

addressed a brief lecture to the members of the International

Theological Commission. He began by remarking on the recent document of that

commission relating to the question of the salvation of un-baptized infants, of

which by any calculation, including the aborted ones, there are many. I will

not go into that question here though the pope did give the principles on which

any solution must be based: 1) 'The universal saving will of God, 2) the

universality of the one mediation of Christ, 3) the primacy of divine grace,

and 4) the sacramental nature of the Church' (L'Osservatore Romano, October 17, 2007). This solution recalls the

document Dominus Jesus that Pope

Ratzinger authored while he was head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of

the Faith. Modern theology is full of those who would save everyone but without

the mediation of Christ, grace, or sacraments. Such theories, however well

intentioned, are not Christian in origin.

Read the entire article...

Wednesday, October 24, 2007

My Bad

Materialism and the moral argument – Part 2: "

SDG here (not Jimmy) with more on materialism and the moral argument (continued from Part 1).

Suppose you see me bullying a weaker party, and you confront me, saying: 'Stop that, you louse!'

'Louse?' I reply. 'Louse? A small, wingless insect of the order Anoplura? I'm afraid I don't know what you're talking about, friend. No no, I'm familiar with the slang usage, of course, but you're quite mistaken, I assure you. I don't feel lousy at all! Never better. You may be thinking of the sorry specimen here at the receiving end of my bullying, who has surely had better days.'

And, indeed, if by 'like a louse' you were only describing how you would feel if you bullied the weak, then your calling me a louse would seem to be a case of sheer projection, as much as my saying 'Stop making yourself nauseous, you fool!' when in fact you love haggis (or whatever).

On the other hand, if at this point you continue to maintain that, whatever my emotional state, there is some meaningful sense in which I am a louse, or that in some sense my lousiness is not contingent upon my own feelings or yours, then we will have to seek further for what exactly it is that we mean by 'lousiness' beyond one or another person's bio-electrical-chemical responses.

You might make a stab at reasoning with me: 'But look here,' you say, 'of course you wouldn't want to be bullied yourself, would you? Why should you treat someone else in a way that you yourself wouldn't want to be treated?'

But I reply, 'Why, obviously, being bullied makes me feel bad, but bullying others makes me feel good. You aren't making any sense at all. Surely you aren't suggesting some sort of quantifiable correlation between bullying or not bullying others and a higher or lower incidence of being bullied or not bullied oneself? I know people say things like 'What goes around comes around,' but don't let's kid ourselves. What correlates with being bullied is weakness; what correlates with not being bullied is strength. I, fortunate that I am, happen to rank in the upper percentiles of the strong — not strong enough to escape all bullying, perhaps, but strong enough to be the bully more often than not. So. There you have it.'

If I were in a tolerant mood, I might even be willing, for the sake of discussion, to allow that if it were possible somehow to make a deal with the universe such that abstention from bullying would entitle one to exemption from being bullied, under those terms I might possibly (reluctantly) be willing to forgo the pleasures of bullying others in order to secure for myself a lifetime of freedom from being bullied. No such terms being possible, though, that would seem to be the end of that discussion.

Where can we go from here?

I should perhaps point out that nothing I have thus far said tends toward some sort of live-and-let-live moral relativism in which bullies should be allowed to bully and we should not stop them, because different strokes for different folks. Different strokes for different folks perhaps, but that would seem to include the preferences of those who like to stop bullies as well as those who like to bully.

So far, for all I can tell, it would seem that all impulses and desires are in principle equally actionable, in proportion to their strength and in inverse relationship to any counter-impulses or countervailing considerations; and so if we like stopping bullies, bully for us.

We are even, it seems to me, free to hate and despise bullies if we wish (or to forgive them, whichever floats our boat). Let's not have any nonsense about loving the sinner and hating the sin (I mean, unless that's your thing). We can even choose to label them (or their actions) 'evil' from our point of view, just as I may call haggis 'disgusting' because that's how I feel about it, irrespective of how you feel.

Having said that, it seems to me helpful to have a vocabulary to describe areas such as long division and history and quantum physics in which different people's answers can be weighed against one another and some found wanting in relation to others, not according to the personal preferences of the judges, but by some more meaningful standard that applies to everyone and everything being judged.

'True or false' might be a start, helpfully supplemented by subtler terms like 'more nearly true' and 'more clearly false,' 'better or worse,' 'more accurate,' or 'more adequate,' or less, etc. Thus, your quotient is right; hers is wrong; how any of us happens to feel about it is irrelevant. Some estimates of the death toll of the Holocaust are better than others, and some are wholly inadequate and even reprehensible. The advocates of various proposals may (or may not) be equally sincere, but the question is not about that.

I hasten to add that dealing with facts doesn't mean that we can necessarily say with certitude, or even at all, what all the facts are, or that there is no room for honest disagreement and different points of view. What exactly happened to Jimmy Hoffa? Is string theory 'not even wrong,' as Peter Woit has argued? Those may be questions we aren't prepared to answer definitively here and now. The point is, whatever the answers are, they don't hinge on your feelings or mine.

Back to lousiness. Is there anything to be said for 'Stop that, you louse!' as anything other than a sheer projection of one person's bio-electrical-chemical aversion-responses on another?

You might take a stab at it by appealing to something like the good of the social order. What's wrong with bullying, you may say, is not that it offends your feelings, but that it harms another person and thus the greater good. That is why society labels me a louse if I bully, not just because of the feelings of any one person.

Now, as a matter of fact the defense of bullying semi-facetiously advanced above isn't especially the kind of thing that an actual bully in a real-world situation would be likely to say, at least as phrased. Here, however, is something that is very much the sort of thing that bullies, when confronted, often say in their own defense:

'We were only playing.'

Bracket for a moment the level of transparent dishonesty of this defense, all but confessed in the very sheepishness or glibness of the tone. Even the bully doesn't really believe he will get away with suggesting that we are all friends here enjoying ourselves in a mutually agreeable and pleasant fashion.

Put that aside just a moment, and consider whether there isn't actually at least a partial but significant level of truth in the bully's defense.

Let me preface these comments with a borrowed line from The Problem of Pain: Let no one say of me 'He jests at scars who never felt a wound.' I am the last person in the world to make light of bullying. In childhood I was not only consistently the bullied rather than the bully, I was at the very bottom of the bullying hierarchy, the bullied of the bullied, and for years the oppression I faced was regular and merciless. The morning walk to school in those years was for me full of dread over the coming confrontations, praying, praying to be spared that day.

For all that, I was never badly hurt, and seldom hurt at all. I know some victims of bullying are, but I think my experience is far more typical. The bullies were out to aggrandize their own egos at my expense, but not to do me any real harm. There was real malice in it, but the goal was to enjoy my fear and their sense of power. The claim that they were 'only playing,' while odious, is actually more nearly true than it might initially seem.

What's more, as intense as my fear was, I can't see that it has inflicted any lasting harm on any measurable level. Having been bullied seems not to have affected my long-term prospects for happiness and success.

For some years in school, I may have been among the least happy in my class; today, well, I just might be the happiest person I know. I'm well-educated, I have a good job and rewarding occupations, I'm blissfully married to a domestic and maternal goddess, and — perhaps most importantly from a materialist–naturalist perspective — we have five beautiful and intelligent children who have excellent prospects of success in life as productive members of society.

By nearly any Darwinian measure, I think it's safe to say I've been rather successful. My experience of bullying was intensely unpleasant while it lasted, but I can't see that society's interests or even my long-term good were ever particularly at stake.

That's not to say I don't think bullying a great evil. I do. I just don't think it's rooted in whatever measurable phenomena, if any, may be adduced under any such rubric as 'the greater good of society.' I think the evil of bullying is rooted in the dignity of the human person, which as I conceive it is bound up in a whole trans-materialistic understanding of human nature and the meaning of life and so on.

That is to say, I regard the dignity of the human person as the sort of subject that transcends individual feelings or preferences, much like long division and the exact circumstances of Jimmy Hoffa's death. Different people may have different interpretations of the evidence; some understandings will be closer to the truth, and some are further, even if no human authority can definitively settle which answers are the closest. But we are talking about something real, not about personal feelings yours or mine.

Continued in Part 3

"(Via JIMMY AKIN.ORG.)

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

Living in a Tiny House

We got the beginning lecture on the (infamous) violinist of Judith Thomson. We are being taught to recognize and evaluate arguments by analogy. She uses three, actually, in that article: the violinist, the rapidly growing baby in the tiny house, and the person-seed problem. There's no problem with her imagination

.One of the fascinating and intellectually challenging aspects of her most famous analogy is that it ignores the possibility that philosophically-rigourous pro-lifers (the "extreme view") might agree that you could disconnect yourself from the violinist and be morally justified.

In our first reading, Noonan alludes to the Catholic position on abortion, which Thomson indirectly identifies as the extreme form (by citing two popes and Noonan while discussing it). The idea of abortion to save the life of the mother (the object of Thomson's "rapidly growing baby" analogy) has long been accepted in Catholic thinking (precluding here from what, exactly, is theology versus philosophy). In traditionally Catholic countries, with the strictest laws on abortion, saving the life of the mother was (is?) permitted. The philosophical and theological insight, however, is that directly killing the baby/child/fetus is always wrong.

Which brings us the principle of double effect: a form of moral reasoning that deals with seeming dilemmas, like ectopic pregnancy, cancer of the uterus, or, for the more imaginative, the trolley problem. We have already discussed in class the idea that a single action may have multiple motivations--a potential problem for Kantians. It is also true that a single action can have multiple effects.

The principle says that if an action, by itself, is good in it's intent and form (some actions are, in and of themselves, immoral; such as directly killing an innocent human being), but it has an undesired, but inevitable, bad effect, that action can be moral. The prime example would be removing an ectopic fetus to save the life of the mother (as distinct from directly killing, then removing it). The death of the child is inevitable, but undesired. Saving the life of the mother is a good. Therefore, so the reasoning goes, this operation is morally justifiable.

Even a slight modification of the Rapidly Growing Child analogy makes it acceptable to almost all pro-lifers: removing the child, knowing that it will die inevitably, to save the mother's life. It's curious that this is the only one of Thomson's analogies that actually speaks plainly of killing. The other two are more antiseptic: disconnecting the violinist and removing the "person plant". Could it be that Thomson, in 1971, wanted to justify as many abortions as possible, but felt it necessary to disguise, somewhat, what actually happens in almost all abortions?

Lies, Damned Lies, and...

Planned Barrenhood does violence to the unborn and to the truth...: "

...about the worldwide statistics regarding abortion. Marcel of 'Aggie Catholics' examines some of the numbers recently produced by the Guttmacher Institute, a research wing of Planned Parenthood, and finds that they don't add up.

"Monday, October 22, 2007

Point-Counterpoint

In the 'The exodus from the Tower of Babel,' Marco Visscher writes in Ode magazine that it's probably a good thing for world peace that 50 percent of the world's 7,000 languages are threatened with distinction. Contrary to the alarm sounded by the National Geographic Society and the Living Tongues Institute, Visscher's brief commentary suggests that, 'just as extinction of several European currencies ultimately yielded economic and practical advantages, the same applies--to an extent--to the extinction of languages.'

Parents in Lausitz, on the border of Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic, would rather teach their kids German than traditional Sorbic simply because German will help them' get on in the world. A forgotten language should be seen as signalling rather than causing the loss of cultural identity.

Language was conceived so people could understand one another. In a world in which people are increasingly connected and work in close co-operation, it is only logical that the need for local languages would fade.

More to the point, less confusion in our Tower of Babel is conducive to world peace. How different might things be if Israelis and Palestinians could--literally--understand each other?

Well, just ask the Catholic and Protestants in Northern Ireland. What's the optimum number of languages we need to go extinct? 6,999?

"Jimmy Akin and Moral Philosophy

Materialism and the moral argument - Part 1: "

SDG here (not Jimmy — but you already knew that, didn't you?) with the first in a series of posts on materialism and the moral argument, adapted from a semi-restricted discussion in another forum.

This post, and those to follow, were originally occasioned by a discussion around what has been called the 'New Atheism,' i.e., the militantly anti-religious, naturalist‑materialist polemics of the likes of Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris.

Discussion around this issue has focused on a number of interrelated subjects, including arguments regarding design, miracles, revelation, theodicy, and morality.

Here is how one Christian board member put the moral argument to a self-proclaimed 'bright' (a loopy self-designation intended, like the hijacking of 'gay' by homosexuals, to co-opt a positive term to replace negative terms like 'atheist'):

If the final answer is really 42 and survival is really of the fittest, then what does it matter if the strong take what they want from the weak? The feelings of the weak are irrelevant because the weak are irrelevant. If I am having a slow day and I fancy a spot of raping and pillaging before supper, where's the harm? After all, when I read the morning news or look back over human history, raping and pillaging would seem to be perfectly normal human pastimes. Everybody is at it. Sometimes even whole nations!

To this, our 'bright' (who calls himself Archie) responded:

I'm sorry, but I grow weary of this kind of argument. If your morality is based on your religion, what stops you from copulating with your daughters (like Lot)? What stops you from stoning people to death with stones, for gathering firewood on the Sabbath? Why don't you make a pact with your god that if you win your next war, you'll sacrifice the first living thing that comes out of your house, even your daughter (like Jephthah)? Why don't you gag your women before they go into church (following the apostle Paul)?

The real truth is that religion and morality are two totally different things, and there are a great many examples of people who adhered to one and not the other. If you like, I am strong, and the thing that stops me bullying weaker people is that I'd feel like a louse afterwards. I will not indulge in that kind of behaviour. Simple.

Now, deep breath, everyone.

Rather than get sidetracked by the transparently silly exegetical aburdities, I decided to take this post as a springboard for some prolonged discussion of the moral argument. What follows is the first post from this series; in the days to come I will follow up with subsequent posts.

First, let me point out that the burden of the moral argument for non-materialists is not that atheists must be bad or even amoral people, or that they have no basis of knowing right from wrong.

Theists generally and Christians particularly do not believe that morality is something that we come to know solely through divine revelation — though we do believe revelation may help clarify, supplement and correct what valid but imperfect moral insights we have.

(While I'm at it, I might also clarify that I don't believe that morality is essentially connected, even for theists, with belief in judgment, life after death, heaven or hell. What matters to me as a theist is above all that God is, and who he is — not how he may reward or punish me. In principle, I think I would still feel that way even if I believed that death were the end. More on this some other time, perhaps.)

At any rate, the point is not 'Unless you read it in the Bible (or unless you hear directly from God in some way, shape or form), how do you know right from wrong?' On the contrary, the Bible itself says that the moral law is written on the human heart (Rom 2), and no theory of biblical authority is required to hold a more or less converging opinion on this particular point.

Archie: You say, 'If you like, I am strong, and the thing that stops me bullying weaker people is that I'd feel like a louse afterwards.'

Fair enough. I can accept that, as far as it goes — at least, insofar as I prescind from whatever epistemic or ontological claims may or may not lie behind the phrase 'like a louse.'

To bracket a caveat or two, this is of course not literally what you mean; I doubt if any substantial connection could be maintained between whatever feelings you might have and any of the small, wingless insects of the order Anoplura.

In slang usage, according to the dictionary, 'louse' can mean something like 'contemptible person, esp. an unethical one' — an affective definition that doesn't help us out with clarifying the actual denotative value, if any, of the judgments underlying these classifications.

To some, in fact, it may seem as if what you are saying essentially boils down to 'I will not act in what I consider to be a contemptible fashion because that would make me feel like a contemptible person' — which would seem to be a rather circular and tautological way of putting things.

What does seem clear at any rate is that 'like a louse' feelings represent an undesirable state of affairs, an unpleasant experience contrary to a general sense of well-being. On its face, that is a perfectly respectable factor to take into consideration for deciding between or among possible courses of action. Unpleasant feelings are, well, unpleasant, and all things being equal, we would prefer to avoid them, thank you very much.

But of course all things are not always equal. A given level of unpleasantness by itself is not always enough to deter us from a particular course of action; and that too is entirely reasonable.

Potential causes of experiences of unpleasantness are many and greatly divergent. Some represent harmful behaviors, such as cutting oneself with razor blades. Others do not, such as eating some food that you personally find revolting.

Sometimes incentives to do a thing are substantial enough warrant facing up to even very formidable unpleasantness without compunction or misgiving, such as going to the dentist for necessary dental surgery. Other times, the unpleasantness even of contemplating a given course of action is so appalling that such action would be simply out of the question, such as being sexually intimate with a person whom one finds physically and personally repulsive.

When it comes to the unpleasantness of 'like a louse' feelings (or guilt, or other potentially morally charged affective responses), in many cases it's easy to see that such responses may be far from random or irrational, as far as they go. There is often a perfectly empirical dimension to old moralistic observations about virtue being its own reward and vice is its own punishment. Even on an entirely materialistic worldview, certain behaviors will tend to correlate with greater happiness, and others with greater unhappiness.

For example, heavy alcohol abuse might make you happy for a few hours at a stretch, but in the long run it is going to cause you more unhappiness than not — and not just because you may feel 'like a louse' afterward (although that may be one factor).

The virtue of moderation commends itself, at least to an extent, to the materialist and the supernaturalist alike, and for many of the same reasons. When Hitchens tries to explain morality by saying 'We evolved it,' it may reasonably be felt that there is at least partial justification for something like what he is saying.

Even when 'like a louse' feelings happen to be associated with an activity for which we can find no rational basis for such feelings, it may still be reasonable to choose to avoid irrational but unpleasant feelings in the absence of sufficient motivation in the opposite direction.

Suppose a boy is brought up in strict Fundamentalism and taught to believe that card-playing is evil. Later in life, throwing off this belief (whether by coming to a more balanced faith or by abandoning faith altogether), he finds that he quite enjoys cards while the game is in play — but afterwards, despite himself, he can't help feeling down. Intellectually he knows that cards aren't evil and there is no reason to feel that way, but he can't shake the irrational 'like a louse' feelings that his upbringing has instilled in him in connection with them.

All things being equal, he might reasonably decide that the fun of playing cards is not worth the irrational depression that follows (though he might also decide otherwise, given a sufficiently strong social motivation, or perhaps a determined intention to root out the emotional consequences of his upbringing).

All to say, the unpleasantness of 'like a louse' feelings can be a reasonable rationale for forgoing even a potentially appealing course of action. So far so good; but how far it goes is as yet an open question.

Archie, you say that bullying the weak correlates for you with 'like a louse' feelings, and thus you will not do it. Fine. I also gather that you find that following what has been called the Golden Rule makes you feel good about yourself, and on one level surely that is justification enough for doing as you would be done by.

And that's fine for you. Of course, what causes one person undesirable feelings may affect another person quite differently, just as a particular dish (haggis, say) may thoroughly nauseate one person while sending another into paroxysms of gastronomic delight. I might be grossed out to see you enjoying a meal that would turn my stomach, but my unquiet gorge has no particular relevance to you or your enjoyment.

Whatever else unpleasant feelings may be, or mean, or tell us, on one level they may surely be regarded as a sort of bio-electrical-chemical reaction in our brains triggering an aversive response. Indeed, on a materialist perspective I'm not sure how else they might be regarded.

Thus, while you might experience negative feelings of sorrow and disapproval to see me bullying a weaker party, what relevance, if any, your bio-electrical-chemical aversion-response has on me or the very different bio-electrical-chemical response in my brain remains to be seen.

To be continued...

"(Via JIMMY AKIN.ORG.)

Sunday, October 21, 2007

Sunday Morning Reading

for science geeks, that is:

13 things that do not make sense: "The placebo effect, dark energy, the Kuiper Cliff, and more. Full article at New Scientist."

(Via New Advent World Watch.)

Friday, October 19, 2007

The Famous Violinist

is the subject of our second reading in Abortion. Originally written in 1971, before the infamous Roe v. Wade decision, it argues against the pro-life position where it is supposed to be strongest: that is, it grants, for the sake of argument, that the conceived being is fully human, a person, fully possessed of the human rights belonging to us all. Thomson then proceeds to show, by means of a now famous thought experiment, that abortion is still a morally right action in some circumstances.

My initial reaction to it, years ago, was that it's artificial. It has little or no relation to the actual circumstances of most abortion decisions.

First off, a mother is proposing to kill her offspring (the literal translation of the Latin fetus) before birth, not a complete stranger. Wikipedia calls this the "Stranger versus offspring objection".

Second, disconnecting the stranger is not a reasonable parallel for what happens in most abortions. (Wiki's "Killing versus letting die" objection.) To make the parallel more realistic (warning: don't click on this if you're at all squeamish), it would involve a third party using a chainsaw and systematically dismembering the offending virtuoso. Or killing the violinist by immersing him in some kind of acid, then removing his carcass. And we don't want to even try to draw a parallel with so-called partial birth abortion...

There are other interesting critiques of Thomson's argument. What interests me is the implication by one philosopher that she abandoned it around 1995 to use another, disputed, argument.

Thursday, October 18, 2007

What Do Linguists Do?

Saving Lost Languages: "This is a story—a creation myth from the Tofa:

In the very beginning there were no people, there was nothing at all.

There was only the first duck, she was flying along.

Having settled down for the night, the duck laid an egg.

Then, her egg broke.

The liquid of her egg poured out and formed a lake.

And the egg [...]"

(Via FIRST THINGS: On the Square.)